How the Legislature Protected Children by Reigning in Texas’ Child Protection Agency

Of all of the state agencies in Texas, Child Protective Services may be simultaneously the most well known and the least understood. Virtually every person knows CPS by name, but very few could describe accurately how the agency functions or what the relm of child protection law looks like.

In criminal law, the death penalty is the gravest sentence that a convict can receive. The United States Constitution and numerous statutes create a closely knite weave of protections for criminals that tightly constrain the state’s ability to dish out such severe punishments. In a word, securing the death penalty is hard, even for the most heanous crimes one can imagine.

In civil law, termination of parental rights is the punishment that is colloquially known as the “civil death penalty.” For anyone whose relationship with their child has been threatened by the state, this idiom is not even remotely hyperbolic. Many people would face jail time or death before losing their child. Similarly, children who are removed from their homes routinely spend years or decades of their life seeking to reunite with their families.

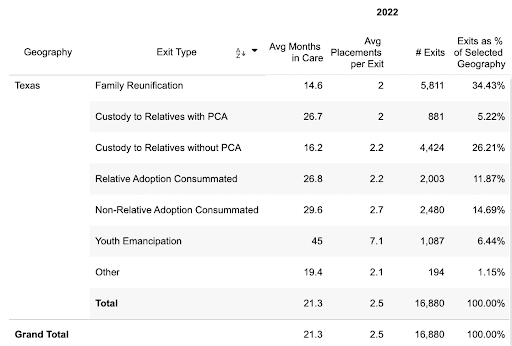

The numbers on child removals in Texas paint a sobering picture. Approximately 225,000 new CPS investigations are launched each year. The law requires that CPS make all reasonable efforts possible to avoid removal of the child and to solve their concerns through some other means. When CPS does remove a child form their home, they are mandated by law to seek reunification of the child with their family as their number one goal. Even so, once a child is removed from their family by CPS, they stand only a 35% chance of ever returning home again. This means that 65% of children removed by CPS never go home. Even for the few children who are reunited with their families, it will be, on average, after more than 14 months of separation.

* Note: Data retrieved from the DFPS Databook. Family Reunification describes the exiting of the child from the CPS system and the child’s return to their home. Data from DFPS over the last few years shows that only 30-35% of children are ever reunified with their family.

The enormous scale of child separations from their families, and the incredible trauma inflicted on children and parents alike, might be easier to swallow if the outcomes for children in foster care were good. But since 2011 Texas CPS has been embroiled in a federal lawsuit over the abhorrent conditions of the foster care system.

In a 2015 ruling, Federal Judge Janice Jack declared that the conditions which foster care children were subject to amounted to a violation of their constitutional rights. “All the while, Texas’s … children have been shuttled throughout a system where rape, abuse, psychotropic medication, and instability are the norm”, she wrote in her opinion. Sobering reports have circulated about children in foster care being funneled into child sex trafficking by opportunistic criminals on an alarming scale.

Judge Jack described the state of the foster care system poignantly in 2015 saying that children “often age out of care more damaged than when they entered.”

And yet, for years the State of Texas’ policy on protecting children from abuse and neglect seemed to conceptualize child removal as some kind of passive intervention–a way to suspend time, separate the child from their family, and quietly reverse it later if it turned out nothing was wrong. It was the “safe option” if a judge or caseworker was unsure about the state of the home. Nobody wanted to be the one who failed to remove a child from an unsafe environment. When in doubt, removal was the safe option.

In the last 6 years, that mindset has slowly given way to a tidal wave of legislation reigning in the power of CPS. In the mind of the reformers, one simple point encapsulates the issue: When you remove a child from their home, you cause guaranteed trauma. Therefore, removal should only take place when the risk of harm in the home is greater than the harm inflicted by removal.

The rules for removal of a child by CPS were so loose and CPS held such outsized power over families that once they were in the CPS crosshairs, innocence didn’t necessarily save them.

In 2017, Texas removed nearly 20,000 children from their homes. That same year, the legislature got serious about child protection. During the 2017 legislative session, the Family Freedom Project (FFP), Texas Association of Family Defense Attorneys (TAFDA), Parent Guidance Center (PGC), and the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) coordinated a massive effort to construct and pass a long list of reforms reigning in the power of CPS. Conservative State Representatives James Frank (R) and Dustin Burrows (R) coordinated together with progressive lawmaker Gene Wu (D) to pack a long list of reforms in House Bill 7.

Among numerous other reforms, the sixty-eight page bill blocked CPS from removing children for seemingly innocuous causes such as being low income or homeschooling a child. The bill prohibited CPS from terminating the rights of both parents when they only possessed evidence against one parent and another provision enabled parents more time to prepare for hearings where they are regularly called to defend themselves on short notice. The bill also required CPS to join cases for multiple siblings together into the same court, rather than forcing parents to fight for the return of each child in separate cases before separate courts.

When House Bill 7 passed, it was seen by supporters as an enormous first step towards rolling back decades of unchecked CPS power which, whether it was wielded with good intentions or not, was producing tangible harm to thousands of Texas families. But there was clearly more to be done.

In 2019, unrelated political battles mostly ground the legislature to a halt, but in 2021, the fight to reign in CPS was front and center once again. Lawmakers passed HB 567, a sweeping CPS reform bill that one lawmaker described as “earth-shaking” to the child welfare system. The bill was constructed over a multi-year period by FPP and the same coalition of partner organizations that had come together in 2017. Once again, conservative Rep. James Frank, now Chair of the Human Services Committee in the Texas House, partnered up with Progressive Democrat Gene Wu, whose law practice in Houston focuses on representing children and parents in CPS cases.

The two lawmakers were able to pull nearly unanimous support for the bill in the Texas House, despite the complexity and gravity of the bill’s changes. On the House floor, Rep. Gene Wu put clear words to the mindset problem in the CPS system that the bill was seeking to reverse. “[T]here is a 100% chance they will be traumatized. . . . We guarantee you if you strip them from their family, they will be traumatized. The question that we’ve never asked is this: is it worth it? . . . it is not worth it to induce a known amount of trauma to a child to offset a possible risk.”

Rep Gene Wu – HB 567

In the Texas Senate, Senator Bryan Hughes shepherded the bill through the process with similar bi-partisan support. The bill was fully passed into law and went into effect in late 2021.

In the spring of 2023, the Texas legislature came to Austin again. Again, FFP and a coalition of like-minded organizations came to the legislature with a list of holes in the CPS system in desperate need of being filled. Among other CPS bills, the legislature passed HB 730, filed by Rep. James Frank and joint-authored by Rep. Genu Wu. In a now familiar story, the two lawmakers carried a nearly unanimous vote for the bill on the floor of the Texas House and, over in the Senate, Senator Bryan Hughes passed the bill through the second chamber with unanimous bipartisan support.

HB 730 now requires every CPS caseworker who investigates a family to provide verbal and written verification to the parent of their rights. Similar to the requirement for police officers to inform suspects of their “miranda rights”, the law now requires that parents be informed of things like their right to remain silent, their right to refuse CPS entry into the home, and their right to consult with an attorney before speaking to CPS.

The bill also took aim at what lawmakers often refer to as the “hidden foster care system” in Texas–a previously untracked, unregulated, parallel system of off-book child removals that CPS frequently obtained by threatening families into “voluntarily” removing their own child from the home for indefinite periods of time. Originally designed to allow CPS and families to temporarily remove a child from dangerous situations without putting the family through a court battle, the practice became so commonplace in the CPS world that some experts estimated that if you add in children who have been removed through these off-book, “voluntary” agreements with families, it would double the size of the foster care system in Texas.

However, once a child is outside of the home, the urgency for CPS to seek reunification with the family is essentially lost, especially with no court oversight or legal counsel to protect the family’s rights. Countless children have languished for months or years in these off-book removals, but HB 730 has now placed hard parameters and reporting requirements on the use of these agreements.

Taken together, HB 7 (2017), HB 567 (2021), and HB 730 (2023) have served as legislative centerpieces in the struggle to more effectively balance the rights of Texas families and children with the sober duties of CPS–and the results have been staggering.

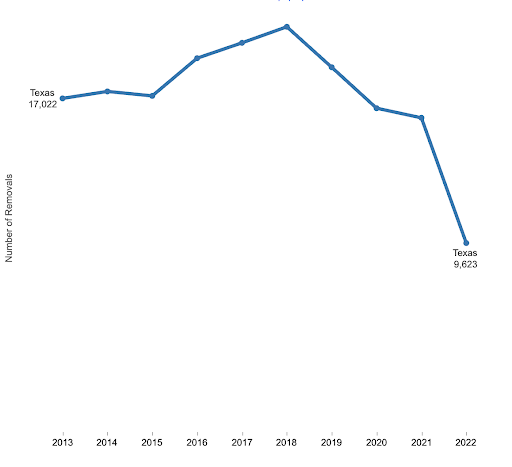

In 2017, the State of Texas removed nearly 20,000 children from their homes. Five years later in 2022, that number had tumbled to less than 10,000–a 52% drop in just 5 years.

* Note: Data is sourced from the CPS databook. Major CPS reforms were passed in 2017 (HB 7) 2021 (HB 567), and 2023 HB 730. During that time, CPS removals of children fell by more than 50%.

The largest single-year drop came between 2021 and 2022 when child removals fell from just over 16,000 down to 9,623. 2021 was the year that HB 567 tightened the definition of neglect to require that children were only being removed if they were found to be in immediate danger of harm, rather than the previous rule allowing removal when there was merely a “substantial risk” that harm may theoretically occur at an indefinite point in the future.

Not coincidentally, also in 2021, there was a dramatic drop in the number of CPS investigations that resulted in “confirmed” findings of “neglectful supervision,” an ambiguous category that critics long claimed allowed for removals for seemingly commonplace activities. That group of cases is the category primarily targeted by the changes to the definition of “neglect” in HB 567. Immediately after the bill’s passage, the number of “neglectful supervision” cases dropped by more than 10,000.

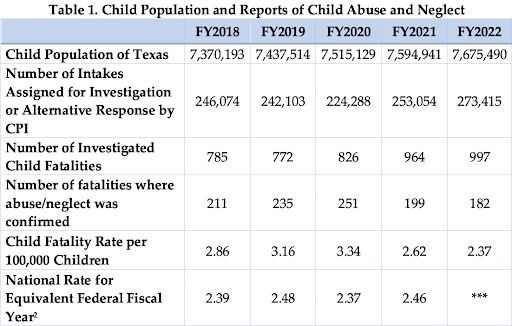

After 6 years of top-to-bottom reforms to the CPS system, 10,000 fewer children are now being removed from their homes per year. Critics of these rollbacks claimed that reigning in CPS could only result in more children being abused and neglected, more children languishing in unsafe homes, and more children dying from abuse and neglect. But during the last 5 years, the rate of child fatalities from abuse and neglect has trended slightly down.

*Note: Data found on page 8 of CPS’s 2022 Child Maltreatment Fatalities and Near Fatalities Annual Report.

This raises a sobering question: if many of the 10,000 additional children previously being removed each year by CPS weren’t being protected from an “immediate danger” in the home, then how many of those families were torn apart by the state needlessly?

In 2019, the Houston Chronicle launched an investigative series called “Do No Harm”. The series recorded the stories of families whose children were torn from their homes over careless and incorrect medical diagnoses. That same year, FFP’s legal team successfully defended a family after their son was illegally removed by CPS in similar circumstances.

When taken together with the last 6 years of data on child removals, stories such as these leave one feeling that it may be far more common than one wants to believe.

Thankfully, the massive attention given to the issue by the legislature is moving the needle–and it’s moving a lot. CPS has the most thankless job in the state. When they are doing a good job, few would know it. When they do a bad job, it’s all over the news.

CPS saves many children from terrible conditions. And yet, the Texas story demonstrates that when an agency like CPS is handed too much power with too few safeguards, it can quickly become a source of trauma to children on a large scale.

In January of this year, Stephanie Muth was named as the new Commissioner of DFPS, CPS’ parent agency. The legislature is giving bipartisan focus on doing better for families. The State of Texas has a chance to set a new course for children, one where a child’s family ties are prioritized and strengthened rather than being neglected and destroyed.

At the moment, it appears we are finally taking that duty seriously.